by Douglass P. Teschner

-originally published in the winter/spring 2004 edition of the Appalachian Mountain Club's Appalachia journal

Love lost, such a cost, Give me things that don't get lost.

Like a coin that won't get tossed, Rolling home to you.

--- Neil Young

May 4, 2003 started out as a pleasant Sunday in Rwanda, where I direct a democracy project assisting that African nation's parliament. Driving rutted dirt roads past banana trees, mud huts, and barefoot women carrying water jugs on their heads, Aussie Paul Dobbie and I discovered a hillside of boulders, a rock climber's mini-paradise. I arrived home after dark pleasantly fatigued, but the good feelings quickly evaporated as I read a cluster of similar email messages. Son Ben described the scene in Franconia Notch: All the TV stations were there, CNN and all. It's really amazing. It was almost like going to a funeral, very sad and a lot of people there. It was a scene of mourning.

I sat stunned for some time until, standing and turning, I found myself staring at the Old Man of the Mountain in winter. I had looked at that photograph every day, but this time was different. The Old Man watched me cry.

I first saw the Old Man around 1960, when my grandparents took me to the White Mountains. That day, the Cannon tramway left a bigger impression. Climbing the 4,000-footers in high school, skiing with my family on Cannon, and later working in the AMC huts, I came to consider the White Mountains a second home. Franconia Notch and the Old Man achieved a commonplace familiarity. But my relationship with the famous profile took on a new dimension when I succumbed to the mystique of rock climbing the 1000-foot high Cannon cliff.

I had done a little climbing in high school with the Worcester Chapter AMC, under the tutelage of Gene Skevington and Charlie Fay, but it did not come easy. Unlike my classmate Eric Engberg, I chose to concentrate on backpacking. It was only on visiting greater ranges, most notably the Atlas in Morocco (where I served in the Peace Corps), that I found a need for climbing skills. I was also impressed by Rob Hall's 1971 and 1972 Appalachia articles detailing the Cannon climbing routes.

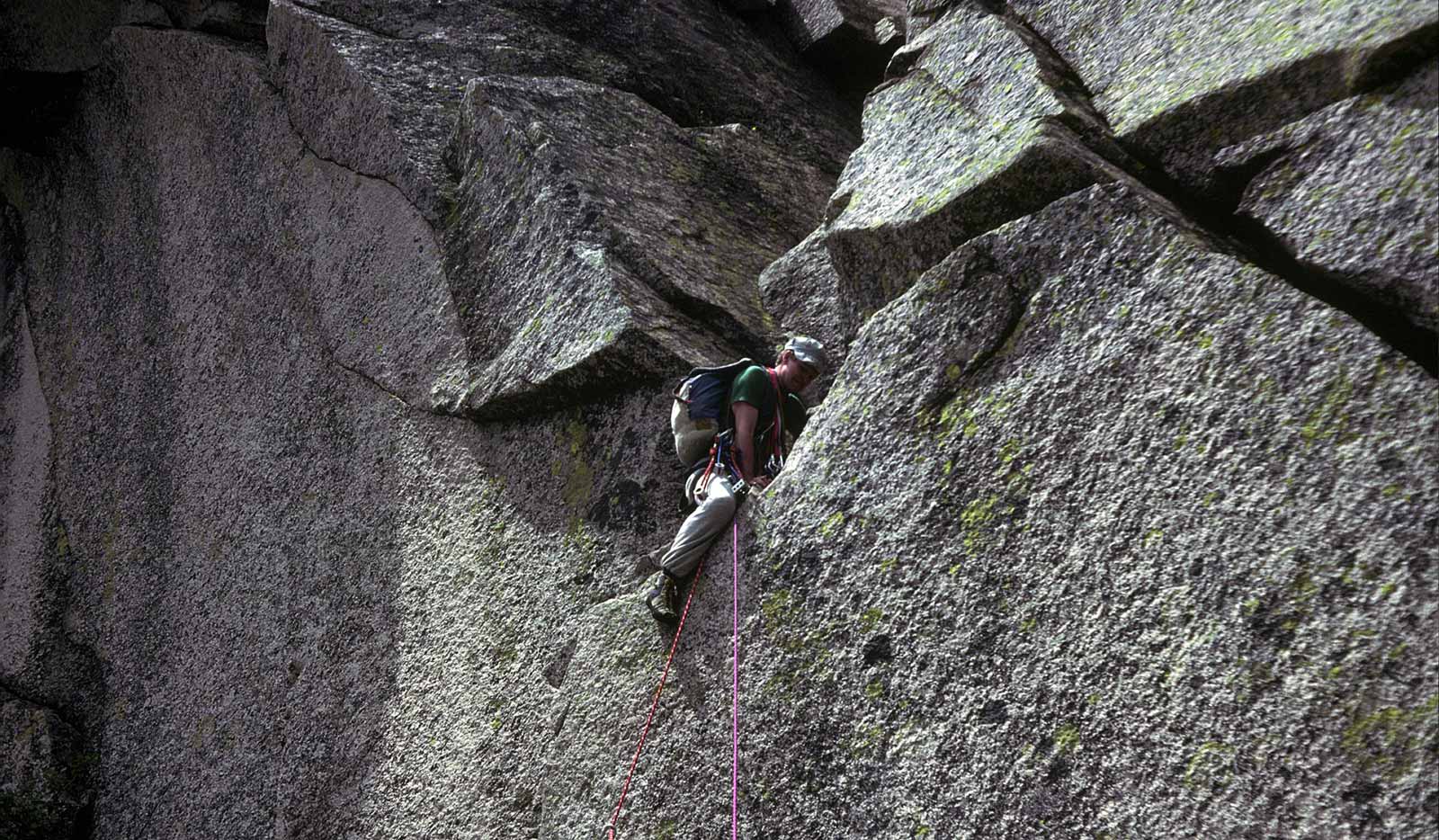

Home from the Peace Corps, I convinced Eric to take me up Cannon, and May 19, 1974 was the appointed day. Clad in vibram-soled Fabiano Madres (a forerunner to today's light hiking boots), an orange 60-40 jacket, and a red crusher hat, I followed Eric and Ed Sklar up the Weissner's Buttress route. Or at least I tried to. I recall several falls, but, hey, this was great: I was a Cannon cliff rock climber! In the late afternoon, Eric warned about the final pitch and suggested traversing off to avoid it. Desire supplanted practicality, and I was soon dangling hopelessly on the au cheval, my every effort making the situation worse. Eric somehow winched me over the hard part, and I finished up the beautiful inside corner in somewhat better form, arriving exhausted atop the Old Man, where Eric belayed, anchored to the turnbuckles. The long drive home was painful: the Old Man had taught me humility.

Rock climbing to the top of the Old Man was first accomplished by Robert Underhill and Fritz Weissner in 1933 as the finish to this same seven-pitch route. Many newer routes on the cliff's right side converge on that same final pitch-the infamous au cheval (also known as "the grunt flake" and "the Hump"). While modest in difficulty (5.6), the awkward nature of the climbing gave it a reputation.

Au cheval is a French climbing term meaning "like on horseback" and mounting this flake is like climbing the edge of an open barn door. A strenuous layback is possible, but the more traditional technique is to straddle the rock flake and wriggle up it, clutching rock between the knees and thrusting and scrapping upward.

Realizing that it would take some work to become a serious rock climber, I found a group of climbers at the University of Vermont, where I started graduate school that fall. By spring, I had nervously led a pitch at nearby Bolton Rock. Come fall, it was time to overcome my fears and return to Cannon.

In October 1975, I convinced Eric to take Ralph Baldwin and me up the 5.7 Whitney-Gilman route. Ralph led the famous "pipe pitch," and I did some leading, too. Jubilantly back down at the dirt pullout at Boise Rock, Ralph and I, plus the newly arrived Doug Burnell (my Peace Corps buddy from Conway), slept the night under the overhanging boulder, where Thomas Boise had killed a horse to save his life.

In the morning, we set off up the rough climbers' trail, first through the forest and then up the impressive talus, to the Lakeview route on Cannon's right (north) side. Despite getting lost on the lower slabs (we climbed something I called "Sideways Chimney" on pitch 2), we made reasonable progress. The next-to-last pitch is a beautiful series of cracks and flakes, with the Old Man hanging over your head. A perfect little crevice at the base of a low-angle slab serves as the belay ledge. The ascent climaxes up the little slab to the au cheval, followed by a majestic inside corner to the top. I had done it! The Old Man allowed me joy.

After that, I climbed Cannon often, especially during the year I taught at the White Mountain School in nearby Littleton. Franconia Notch was our playground, a 15-minute drive from school and better than any gym.

In September 1978, I climbed Cannon again with Eric, this occasion via Consolation Prize (5.8). It was sunny, but windy, and I proudly led the au cheval pitch, an important rite of passage with Eric after our "epic" four years earlier. That may have been the first time I led the steep and airy wall to the right of the final corner, a real heart pounder. The Old Man had shown me that persistence pays off.

While we talk about "climbing to the top of the Old Man," that is not precisely accurate. The au cheval could be called the Old Man's right ear, and the pitch ends about 20 feet higher than the top of the profile, at a three-foot wide epoxy drainage which has kept water from penetrating the many cracks on the Old Man proper. The turnbuckles used as the climber's belay anchor prevent movement of a couple of boulders, which are not actually part of the profile. The more famous turnbuckles, gripping the top of the Old Man's head, are a few feet below.

The late 1970s was my peak climbing period, imbued with passion and adventures both far (Alaska, Mexico, Scotland, the Alps) and near-where Cannon was my favorite cliff. Doug Burnell and I climbed the classic Sam Swan's Song in June 1977, and the easier routes (Old Cannon, Cannonade, Weissner's Dike) were part of our regular repertoire.

In 1981, I disappointed my fiancée (now wife) Marte by insisting on taking newly arrived friends from Seattle to Cannon the weekend before our wedding. We got one pitch up Whitney-Gilman before it started to rain, a kind of poetic justice. The 1986 purchase of our house in Pike, New Hampshire, brought me a mere 40 minutes drive from Cannon, but by then I had a two-year-old son; another arrived a couple of years later. Much of my time became devoted to family, work and politics, with 1988 election to the New Hampshire House of Representatives.

Still, I found time for convergences at various White Mountain cliffs, with Doug Burnell arriving from the east and me from the west. Cannon was a common destination. The top of Cannon cliff became one of my favorite places in the White Mountains, if not the whole world. It has an alpine character with slabs of granite interspersed among patches of alpine flora and thick krummholz. The views across the Notch to Lafayette are stunning, and the tiny cars moving up and down the valley far below elicit a certain smugness from a climber on the heights.

There is a climber's trail along the cliff top that ends at the Old Man, where a more-traveled path leads down to Profile Lake. Except for the Whitney Gilman and some other climbs on the left (south) end of the cliff, all Cannon rock climbers who reach the top pass down by way of the Old Man's head, unless they hike to the summit-a rare but favorite activity of mine. In daylight, the cliff top trail can be obscure. At night, there is a special beauty to watching the headlights down in the Notch, but finding the way across to the Old Man is quite a challenge, as I first found out in 1983 when Doug Burnell and I got caught out after dark near the top of the Duet route.

One hot August Sunday in 1993, I lingered after politicking at the North Haverhill Fair. I never should have taken that ferris wheel ride with son Luke. A few hours later, Jim Morel and I were in darkness high on the Moby Grape route. Although tired, I was motivated to keep moving by the thought of a possible Manchester Union Leader headline: "State Rep Stranded for the Night on Cannon Cliff." We finally got to the fog-shrouded top and eventually stumbled upon the helipad for the Old Man repair crew (then led by my legislative colleague Niels Nielsen). I think it was midnight when we reached the car.

Rain can be another problem, as when Jim and I got caught on the suddenly slippery slabs in 1994. We scrambled off right and ended up totally soaked and cold, bushwhacking down the cliff's right side. When the clouds lifted briefly, we saw the Old Man from a unique angle, stoically and reassuringly peering down upon us.

Newcomers to the cliff also bring a new perspective. In 1997 old friend Ralph Baldwin, visiting from his Alaska home, convinced me to join him in taking each of our oldest offspring up Cannon. On the cliff, I was a nervous wreck but tried not to show it. I gave detailed instructions to 12-year-old Ben at the au cheval, hoping he would avoid my earlier fate. He practically ran up it and, arriving at the turnbuckles, asked, "What was so hard about that, Dad?"

Jeb Bradley did not fare as well and got stuck on the au cheval until I rappelled down and coached him up it. His predicament and persistence gave me a déjà vu feeling and was later immortalized in a Concord Monitor profile on his successful candidacy for the US Congress.

We like to think of rock as permanent: "Like a Rock," booms the Chevy ad. Some New Hampshire granite, like Conway's Whitehorse Ledge, almost matches that image, but not Cannon. A rock fall obliterated sections of the Old Cannon route, leading me to author a 1981 Appalachia note entitled "Death of a Rock Climb." A few years back, a climber on the talus miraculously escaped with his life after being pinned down by rock fall near Duet. Sam's Swan Song was always a "loose" affair, and recent rock fall has made it more dangerous to climb than ever.

Fortunately, most big rock falls occur in the early spring or after heavy rains, when few climbers are present. Around 1998, the most massive of all obliterated a large area in the middle of the cliff (now known as "the Zone of Destruction"), with one large boulder crashing down through the woods to the Franconia Notch bike path.

So why did we think the Old Man, so precariously perched, would be any different? Buried in my file cabinet, I found geologist Brian Fowler's publication of his 1976 research, done as part of the Notch Parkway environmental assessment. Amid diagrams and mathematical analyses of mechanical stresses, he observes, "the stability of the profile is apparently very delicate" and "minor changes... could precipitate collapse of the structure."

Still, it was a tremendous shock when the forces of gravity and erosion took their natural course. In New Hampshire, public grief ensued, with pages of newspaper letters, one writer even saying it was worse than 9/11. There are many excellent rock profiles in the state (at least four in Franconia Notch alone), but, somehow, the Old Man was special. He captured our imaginations and achieved the persona of a father figure-stern but faithful. You could always count on him to be there. And now that faith has been shattered like the chunks of granite far below on the talus. My son Ben wrote, "We are all mourning the loss of the Old Man of the Mountain, who came crashing down from his watchful perch on Cannon mountain some time last night. New Hampshire has lost a member of our community."

A cynic could attribute all this to mere nostalgia or jingoistic state pride. At some level, there is a bit of truth to that. But I also think there is a deeper, spiritual dimension, a connection to the mysteries of nature and God that created the Old Man in the first place.

Three days after the Old Man collapsed, I left Kigali on a long-planned trip home, my first in seven months. I was soon drawn to the Notch and parked at the familiar Boise Rock, crossed the sparkling brook, and turned right on the Pemi Trail. The emerging plants and smells of spring were a joy to the senses. After a steady ascent up the climber's path, I approached the final moment with trepidation. To the left, I spotted two dangling cables, like claws that had forlornly lost their grip on precious cargo. Straight ahead, the epoxy trough was still there, the scene in that direction eerily unchanged from my first visit 29 years earlier. I uncoiled my rope, tied it to the familiar turnbuckles, and rappelled down the corner and au cheval, both fully intact, as I had suspected they would be.

I looked up to the void where the Old Man's face used to be. A brown streak of rubble and dirt, perhaps 300 feet wide, stretched down to the talus 800 feet below. The beautiful next-to-last Lakeview pitch seemed mostly intact, but the middle part of Lakeview and all of Consolation Prize was littered with debris, with much newly exposed rock. As state park ranger Mike Pelchat told a journalist, it will take some time for the Old Man's blood to wash off before that area can safely be climbed again.

I turned and climbed back up with a self-belay, but stopped suddenly realizing I had not attached my harness properly. The horror of realizing that a momentary lapse in concentration had almost killed me strongly diminished my pleasure of climbing the au cheval once again.

Back at the turnbuckles, I said goodbye and hiked up along the cliff top to the outlook connection to the hikers trail, then punched through snow to the summit. Riding the tramway down, I saw the crowd dispersing from the "Family Remembrance Day" ceremonies, a funeral of sorts for the Old Man. At the bottom, I hugged Deb Nielsen, the NH House of Representatives Sergeant of Arms and an official Old Man caretaker, and passed on to Profile Lake, where people milled reverently about. Flowers had been piled below the wooden sign of the carved face that was no more.

A few weeks later, the day before I came back to Rwanda, I touched New Hampshire rock again on Middle Sugarloaf, my favorite backcountry crag. It was a beautiful afternoon in a beautiful place where the green of nearby Mount Hale and the majesty of farther-away Mount Washington set a perfect scene. You could almost smell the sweet granite, which left fingers roughened in a most satisfying way. The hike back down, with the finish along a perfect rushing stream, was a bittersweet combination of quiet satisfaction and sad thoughts of leaving my White Mountains and the steadfast companionship of Doug Burnell.

As I drove back along Route 3 to the cutoff to Easton and the way home, I passed Cannon Mountain and gave one last salute in the direction of the fallen stone face. It was Father's Day, and my wife had given me a T-shirt of the famous profile with the caption "I Miss My Old Man."

The author is a long-time AMC member who has written numerous articles for this journal over the past 30 plus years, including "Percy Adventure" (his first), "Ding 'Em Down" (on the life of an the AMC hutman), and ascents of peaks in Morocco, East Africa, and Scotland. He also wrote and edited "Like Hay in the Wind," an account of death and rescue on Mt. Washington.

Back to Old Man Stories | Home Page